Statistics can help us better understand the social problems that we face. When we look at housing in Scotland, we tend to focus on the figures that show evidence of a housing crisis, such as that over a million people live in relative poverty after housing costs, and that 142,500 applicants are waiting for council housing. Or, that 34,100 households applied as homeless last year, and that at the last count 10,873 households were living in temporary accommodation including an ever-rising 6,041 children. But as shocking as these figures are, they represent the symptoms of housing crisis, but they don’t do much to help us understand what is causing it.

New figures from the National Records of Scotland published this month help to shed some light on the structural factors behind Scotland’s housing crisis. Scotland’s Population 2016 – the Registrar General’s Annual Review of Demographic Trends, is a rich source of information, bringing together data on population, births, deaths, life expectancy, households and housing from a variety of sources. This latest publication is the 162nd edition, and includes an invited chapter on household changes and housing provision in Scotland by Professor Elspeth Graham, Dr Francesca Fiori and Dr Kim McKee which shows some of the housing implications on these changes in our population and demographics. It points to trends towards lower building rates, a growing population and a change to the way people live in households, coupled with changing policies including right to buy.

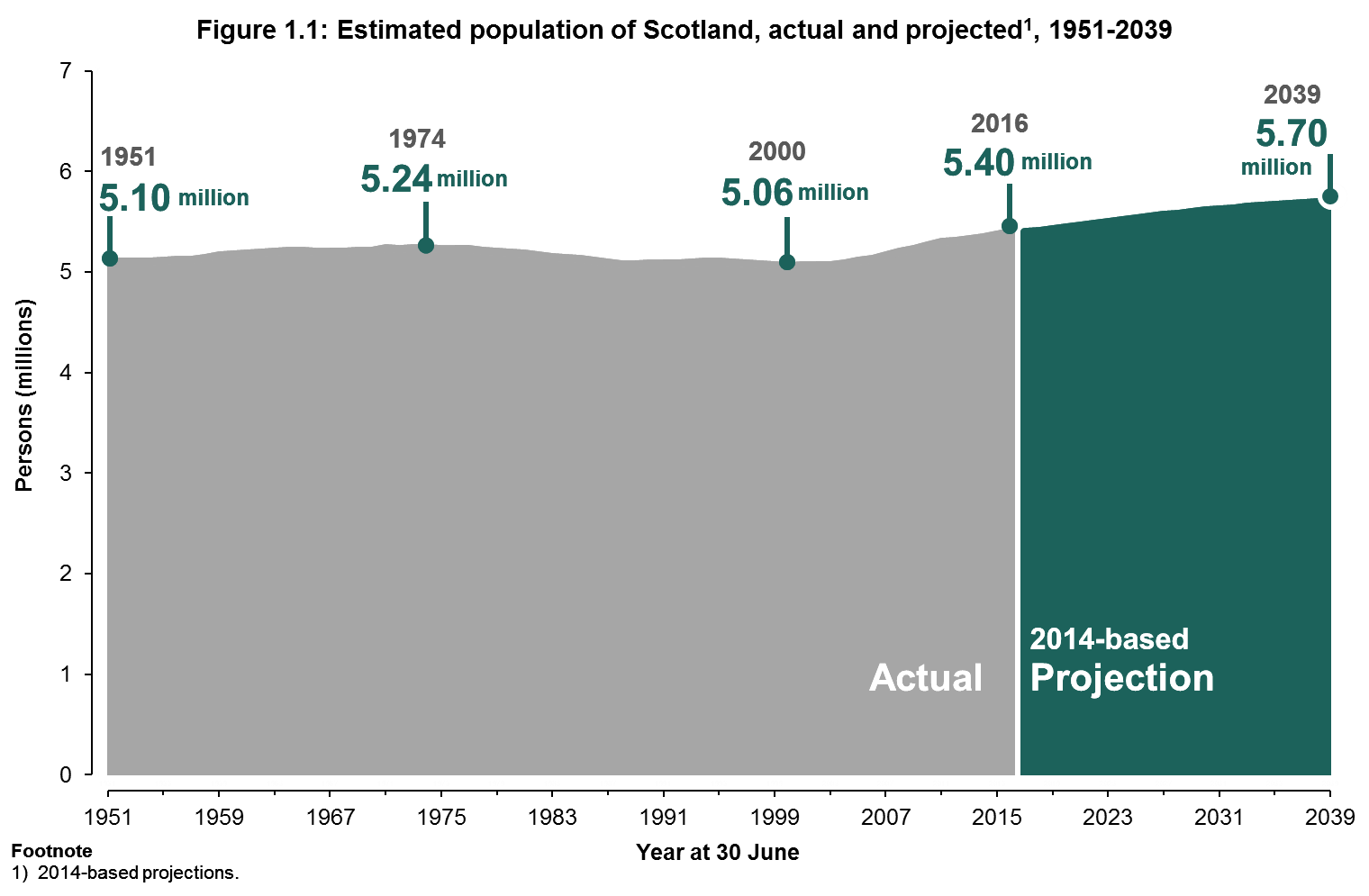

- The population of Scotland is increasing.

In 1951, the population of Scotland was 5.10 million, and in 2016 it had risen to 5.40 million. It is projected to rise further by 2039 to 5.70 million people. And all these additional people need somewhere to live.

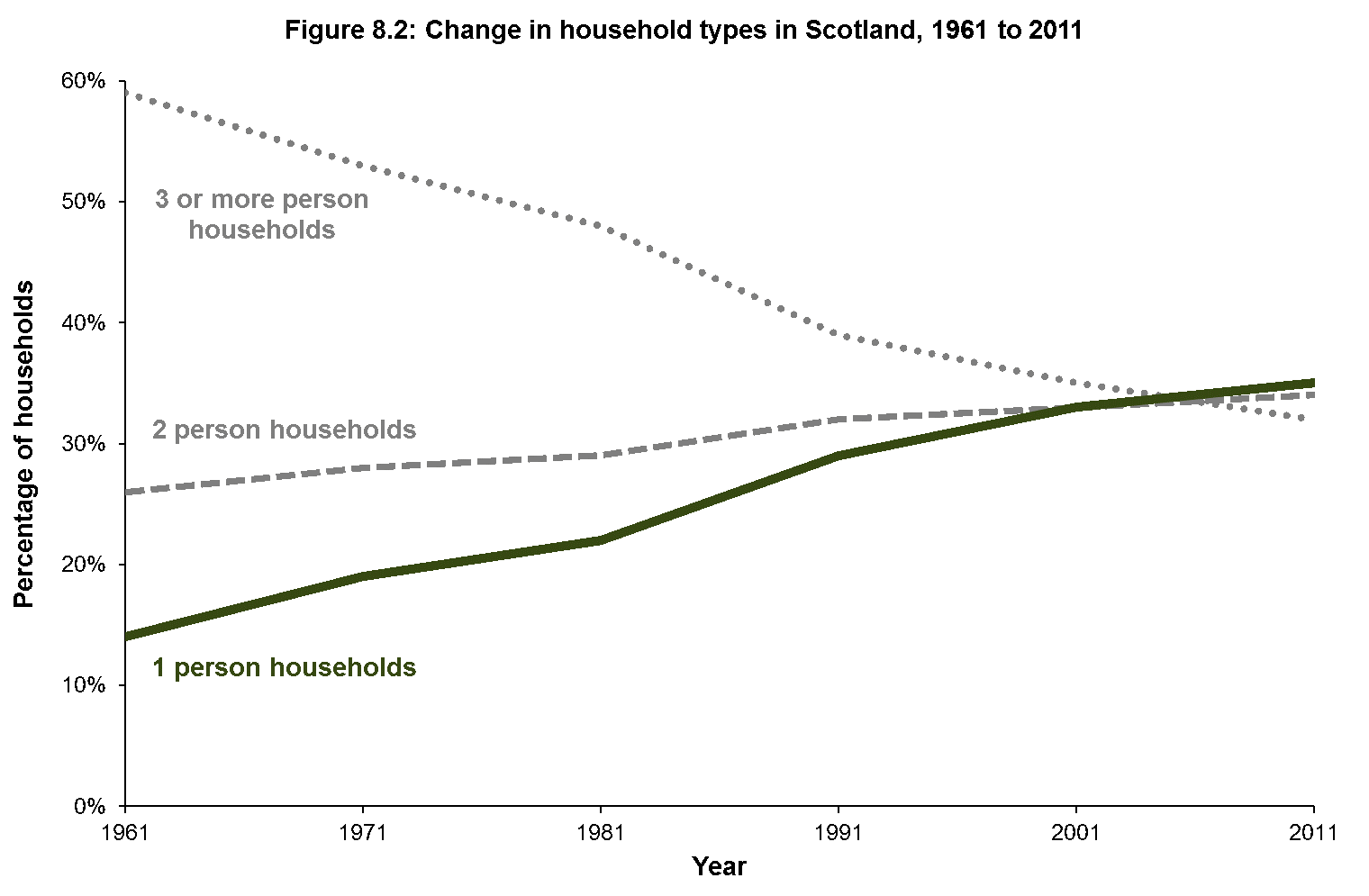

- The number of households in Scotland is increasing even faster than the population – largely because of the growth in the number of 1 person households.

One person households are in fact the most common type of household now, in part due to our ageing population meaning there is a rise in the number of pensioners living alone. This places increasing demand on our housing stock: each of these households requires a home in which to live, and providing homes suitable for older and disabled people living alone becomes vital.

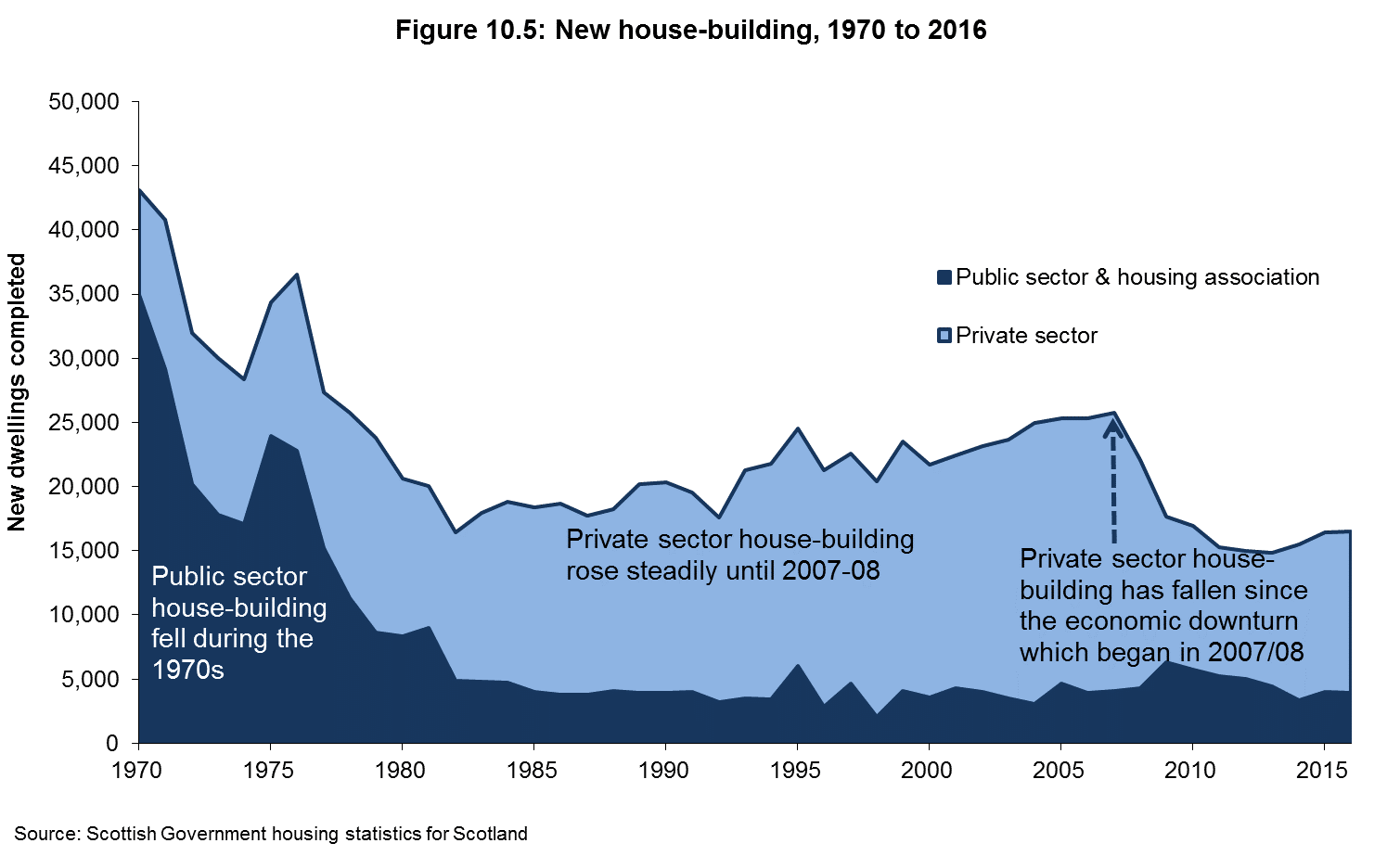

- Despite growing need, fewer houses are being built each year, especially homes for social rent.

In 1970, 8,220 private sector homes and 34,906 public sector and housing association homes were built. Public sector house-building then fell dramatically, and for a while the private sector picked up some of the slack until the late noughties. However, in 2016, 16,498 homes were built – less than half the total in 1970.

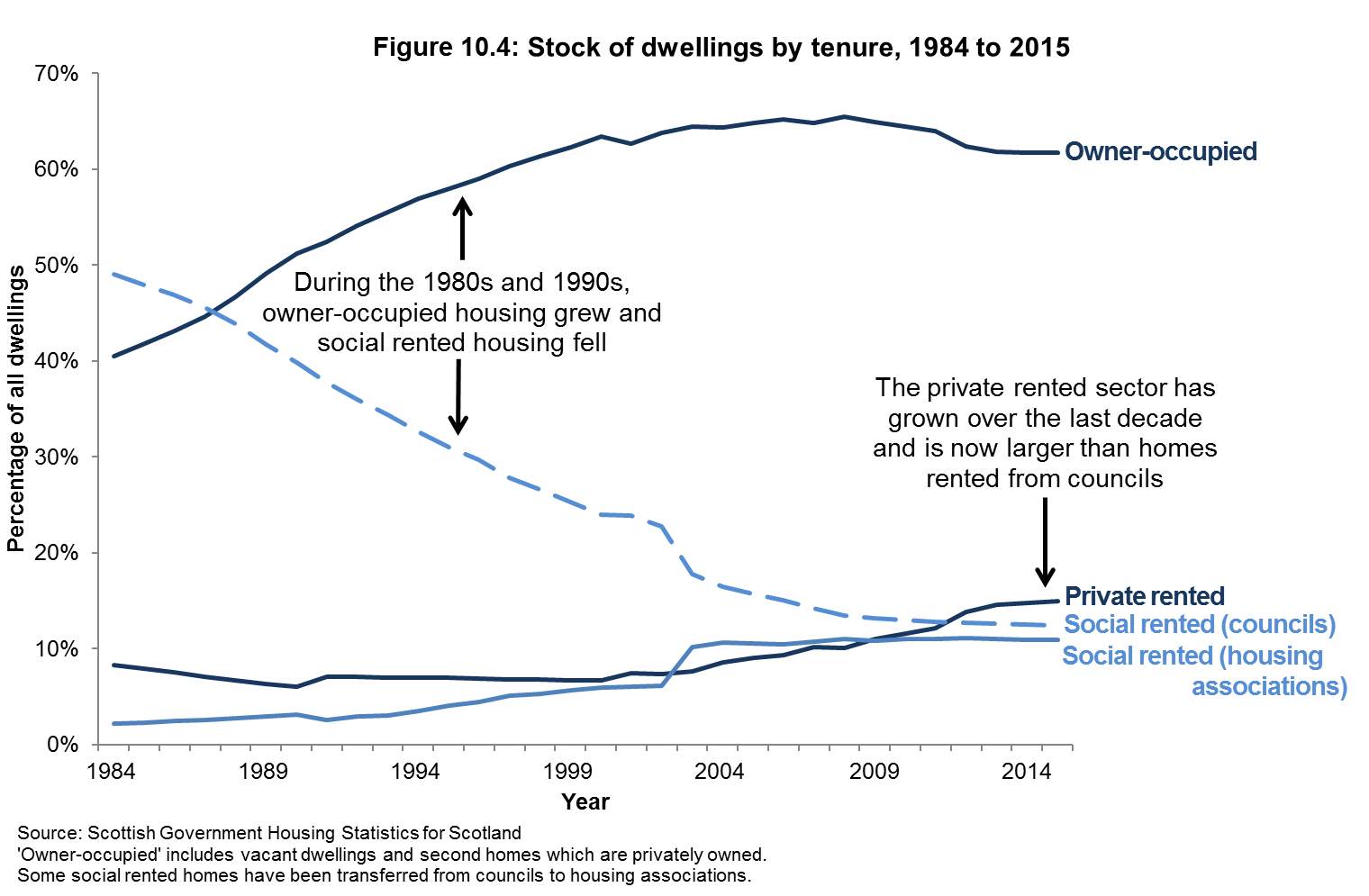

- There is now dramatically less social housing, and there has been a growth in the number of privately rented dwellings.

As a result of a combination of factors, including the change in building patterns, a renewed emphasis from successive governments to owner occupation as the ‘desired’ tenure, and the implementation of right-to-buy, the mix of tenure has changed dramatically with much less social housing and much more owner occupation. The private rented sector has also seen growth as it fills the gap for households who have been priced out of owner-occupation, or who choose not to buy, but for whom social rented housing is also not a feasible option because of the demand on reducing stock. In fact, as figure 10.4 shows, more people now rent in the private rented sector than they do from the council – a dramatic shift given that in 1984 almost half (49%) of all dwellings were council-owned.

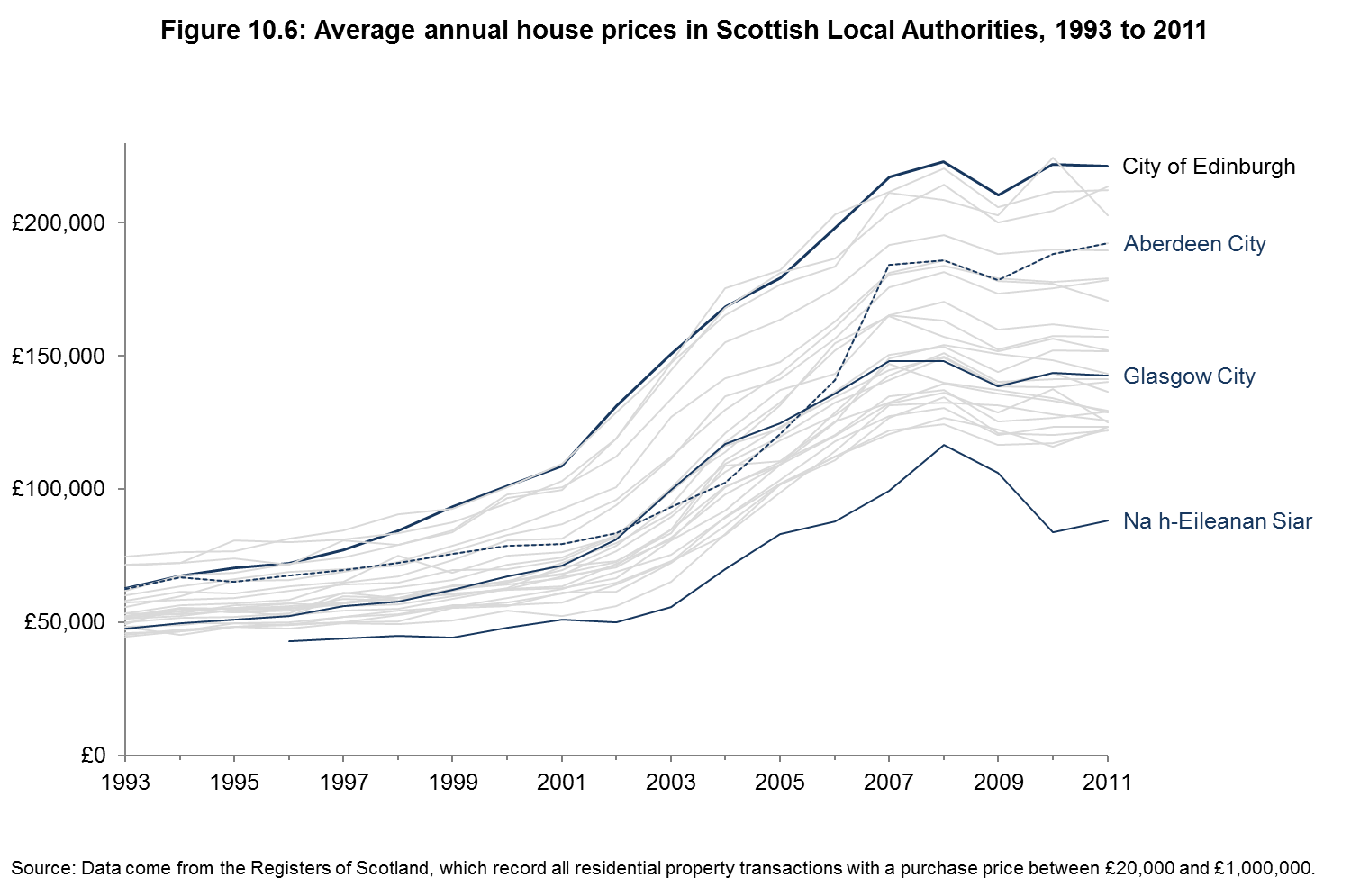

- One result of the increasing demand on housing has been an increase in house prices.

Figure 10.6 shows one of the effects of increasing demand on housing stock via the steep rise in average annual house prices. In Edinburgh in 1993 the average house price was £62,487; in 2011 this had more than tripled to £221,303.

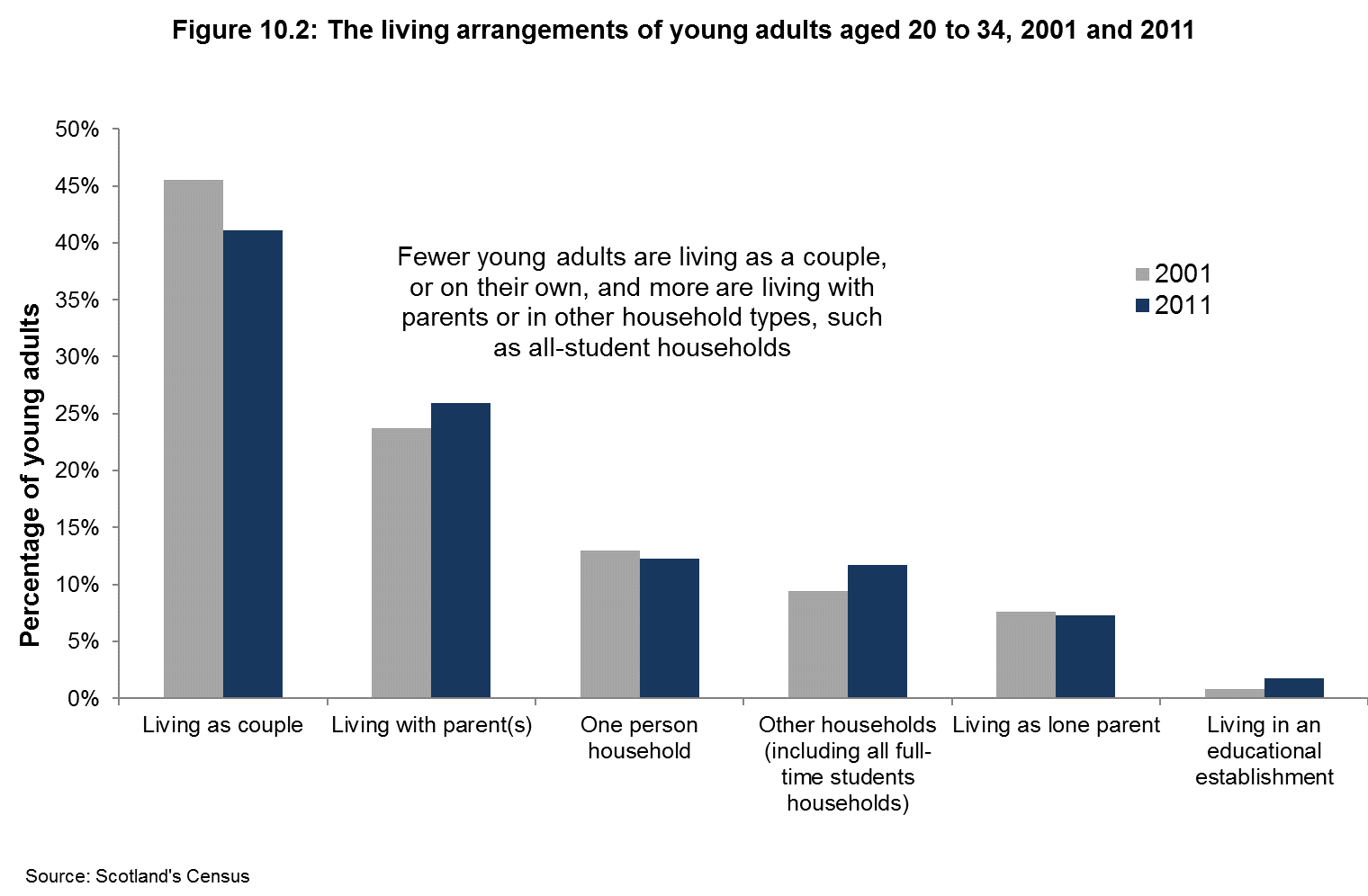

- Certain housing options have become unattainable for certain groups.

Figure 10.2 shows the changing housing destinations of 20 to 34 year olds: more young adults now live with their parents or in ‘other’ households, including in student households, and less live on their own or as a couple.

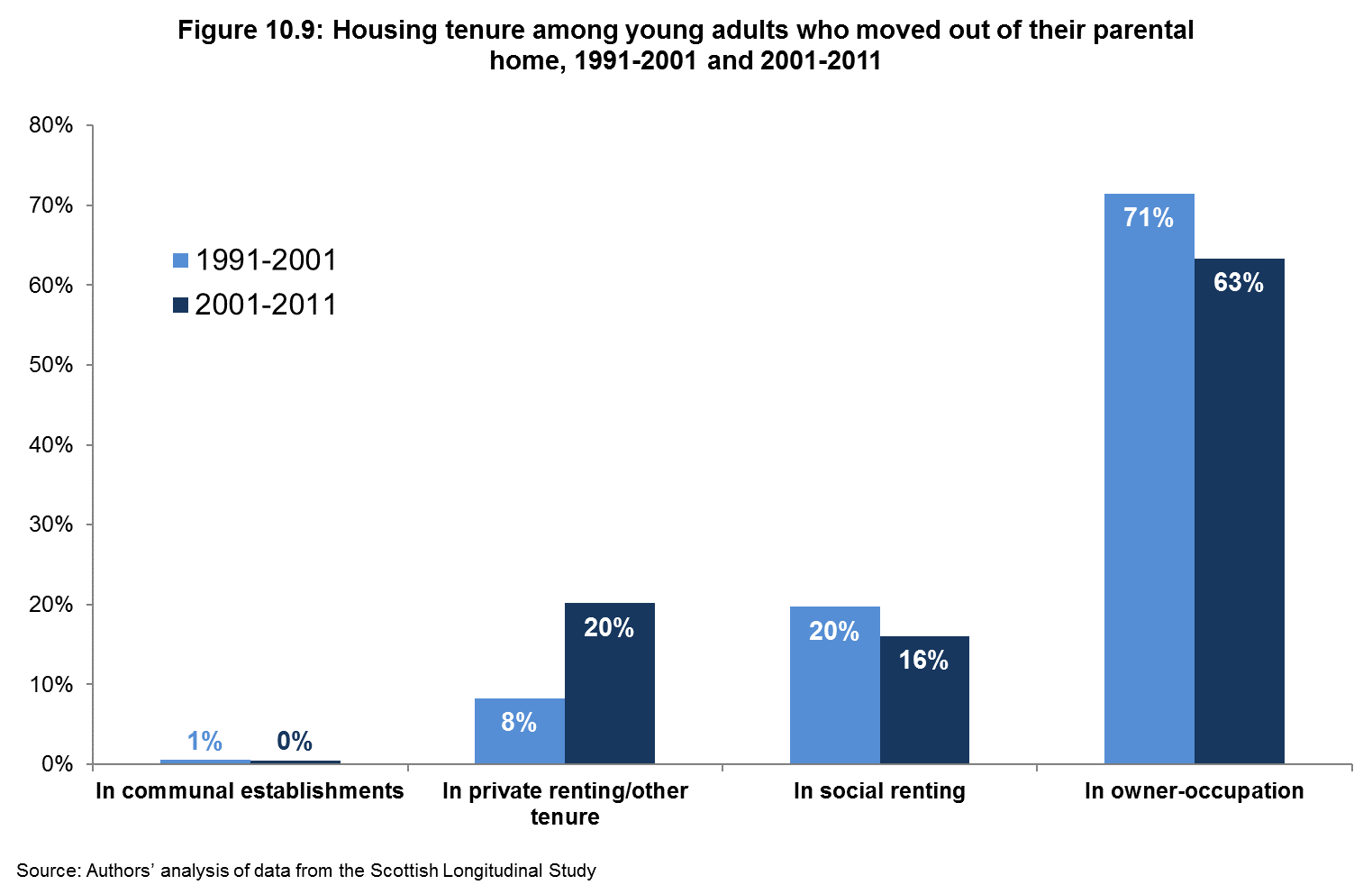

For 16-24 year olds moving out their parental home, more now rent privately and less move on to become owner-occupiers.

These figures don’t tell a new story about the trends in Scottish housing, but they do underline both the scale of the challenge and point to some potential consequences of failing to tackle the housing crisis. The solutions aren’t simple, and shifts in demographics and households are beyond the scope of housing policy. But some of the solutions are apparent and urgent. A good place to start is to deliver a step change in delivery of more affordable housing. Independent evidence on housing need and demand shows that we need at least 12,000 affordable homes each year for the next 5 years. In the meantime, we must ensure we provide a strong housing safety net so that support is available for everyone to keep or find a new home.

This blog post was updated on 17th October to correct a statistic.

All graphs in this blog post taken from Scotland’s Population 2016 – the Registrar General’s Annual Review of Demographic Trends.